Kurashita no Yu (a small mountain hot spring in Hakuba Village, Nagano)

In the changing room filled with evening steam, my eyes were caught.

A man wearing only a fundoshi stood there without hesitation.

For some reason, I could not look away from him.

“Why do you wear a fundoshi?”

I spoke to him without thinking.

“It has no elastic, so it does not stop the blood flow. It also does not trap heat.

When I tie my fundoshi, I naturally think, today I will live straight.

That feeling is what ‘harawo kukuru’ means to me.

When I tie it around the tanden below my navel, my mind settles in a quiet way.”

Behind his smile, his words carried a quiet power.

He placed his daily resolve and prayers beneath a single cloth.

Drawn to that act, I wanted to hear more from him. His name was Terada.

On the way to Kurashita no Yu

Terada-san was born and raised in Osaka.

He loved music and fashion, but at twenty his father suddenly said,

“Come to Shiga and help with the work.”

Confused but obedient, he moved to a place where he had no clear purpose.

He had no friends, and the workplace was closed off. Loneliness was normal.

“What kind of person should I become?”

There was no answer, so he sank into music each night.

On weekends he went to all kinds of events, from big festivals like Fuji Rock to tiny gatherings in the mountains.

He danced as if seeking freedom and searched for himself in the sound.

That path led him to work at an outdoor gear shop.

At first he knew nothing about mountains.

The manager took him hiking, climbing, and camping.

His first real overnight climb was Mount Fuji.

Instead of starting at the fifth station, they began at the first, camped at the fifth, and reached the summit the next morning.

“It felt less like a challenge to the mountain and more like a challenge to myself,” Terada-san recalls.

That experience awakened a new desire in him.

“I want to accomplish something on my own.”

At twenty-three he crossed the Suzuka Mountains over three days.

There was no water on the ridge, so he carried eight liters and a tent across many peaks.

But by midday on the second day, his water ran out because all his meals required hot water.

Thirsty, exhausted, and slipping on rocks, he still pushed forward.

Just before sunset, he found the shelter and shouted with relief.

Beside the hut was a stainless tub filled with rainwater.

He boiled the water, with algae and tadpoles, and mixed in brown sugar to drink.

He endured it, masking the smell as best he could.

“Water… I never knew it was this precious.”

At that moment, Terada-san regained something he had forgotten.

Mountain Ridge

The next year, the Great East Japan Earthquake struck.

The scenes on the screen left him speechless.

Everyday life disappeared in an instant.

He realized he had been living without thinking.

Electricity and water had always been there,

and he had never valued or appreciated them.

With that realization, he decided to quit his job.

He lived in a mountain hut in the Southern Alps in summer and in busy Hakuba in winter.

In the Southern Alps he lived with limited supplies.

Facing nature, he learned skills he could never gain in a city.

It was not to survive, but to live fully.

At twenty-three he learned about the Maya calendar.

It cycles every fifty-two years, with twenty-six as a turning point.

Told he would rise until twenty-six, he made a promise to himself.

“When I turn twenty-six, I will go to Borneo.”

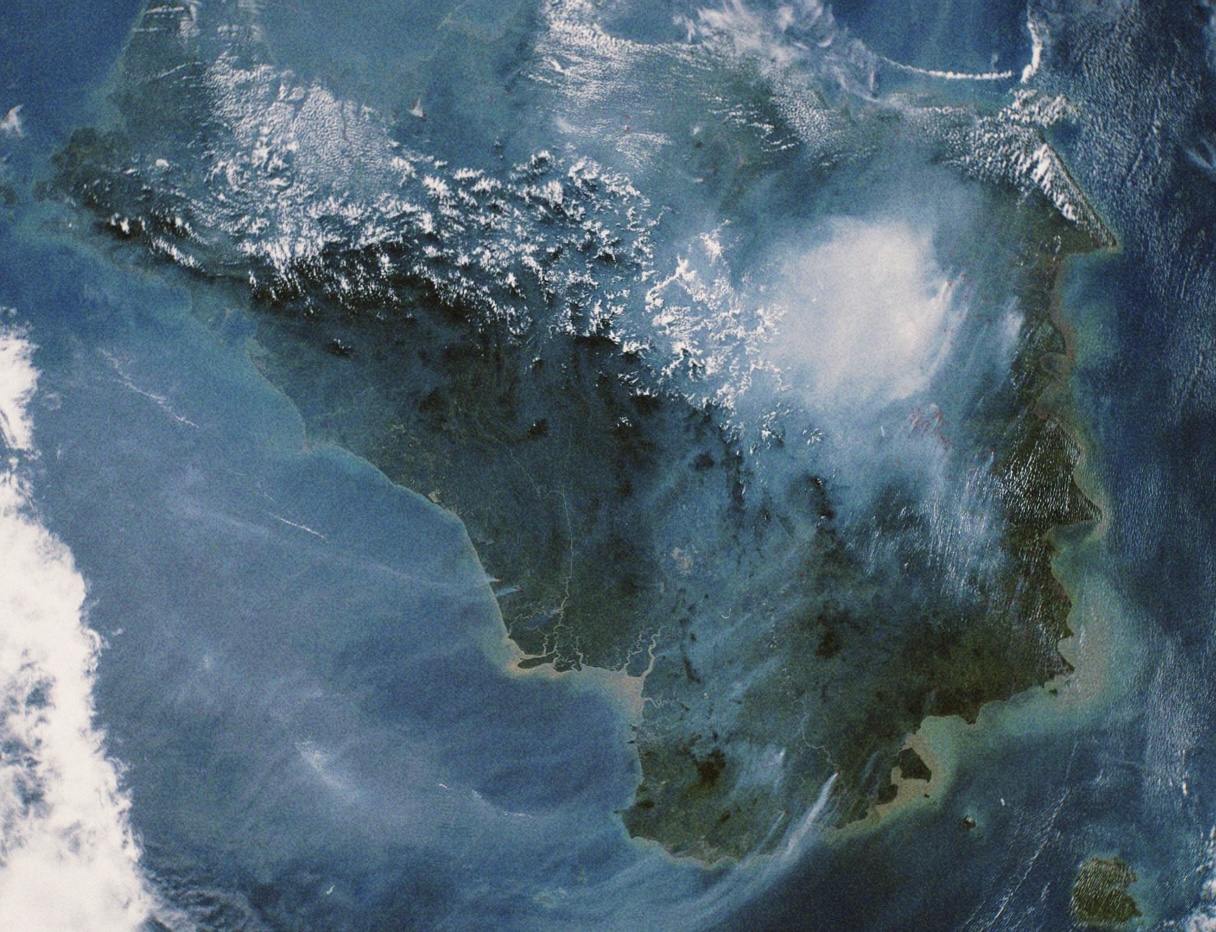

Borneo Island.

Three-quarters belong to Indonesia, one-quarter to Malaysia.

It has remained unchanged for over 100 million years, home to one of the world’s oldest jungles.

He learned of Borneo through a chain of coincidences that felt like fate.

As if destiny had begun before the journey itself.

The final push came from an experience at a zoo in Ishikawa.

An orangutan reached out through the glass for a fist bump.

A reggae lover, he was moved by its innocent gesture.

“One day I will meet a real one.”

That promise guided him to the island.

Borneo Island

At twenty-six.

In the promised year, he left for Borneo.

But on the first night, his phone was stolen while he slept on an airport bench.

Google Maps, translation apps, hotel details—all gone.

He felt cut off from the world.

“I realized how much I depended on that small screen.”

Terada-san says.

In a foreign land, he could rely only on people's words and his own senses.

After searching desperately, he reached a tour office guided by locals. And a miracle happened.

There sat a friend-of-a-friend from his outdoor shop days.

As they talked, the trip began to fall into place.

Before he knew it, it became a private tour found nowhere else in the world.

He met orangutans deep in the jungle, shared meals with villagers, and spent quiet evenings listening to the sun set.

On the way back, he hitchhiked and met a couple.

A Singaporean husband and a Bornean wife.

They treated him to local food, and he asked why they were so kind.

The wife smiled softly.

“I did not want you to think Borneo is a terrible place. I wanted you to return thinking it was the best Borneo.”

Her words struck his heart.

Human kindness becomes the memory of a place.

At twenty-six, he understood the meaning of his turning point.

Back in Japan, he returned to the mountains.

After winter, it was time to look for summer work.

Snowboarder friends went down the mountain each spring to work in tea fields.

He joined them.

He began picking tea in the fields of Shizuoka.

One autumn, after the tea harvest slowed,

a café owner asked him to help with the garden.

A plum tree was weakening, and he was asked to watch over it until a gardener arrived.

Soon, the gardener arrived.

He introduced himself as a gardener and also a surfer.

His easy smile held the same freedom as mountain friends.

“Want to try helping?”

That invitation became his first step into garden work.

Terada-san Focusing on the Garden.

As he worked, he came to love the moments of rest on the veranda.

Holding a tea cup, talking before the green garden, forgetting time.

No clock was needed. Only wind and light moved time.

“I want more people to feel moments like this.”

That wish led to Saniwa, a tea garden café in Higashiōmi City, Shiga.

The tea served at Saniwa comes from seed-grown native trees in the Okueigenji region.

Their history goes back to the Muromachi era, passed down by seed for generations.

Unlike cuttings used in common tea farms, each tree has a different shape and aroma.

Each has a unique character, and no two cups taste the same.

Today such native varieties make up less than two percent nationwide.

Terada-san grows them without pesticides or chemical fertilizers and handles the processing himself.

He trusts nature yet spares no effort.

Each cup carries a life force passed down through time.

The old farmhouse café has large windows looking out to a quiet garden.

Guests enjoy tea slowly while watching the garden change with the seasons.

“In the past, Japanese people shared information over tea. Tea was always at gatherings and celebrations. I hope people can remember that origin here as well.”

- Saniwa -

The Autumn Garden Reflected in the Glass

Terada-san shared a story.

A mountain worker dropped a rice ball,

got lost searching for it, and was taken in by a local family who fed

and sheltered him.

He noticed a damaged pillar and repaired it in return.

“If you convert it to money, a night with meals is at most ten thousand yen. But a pillar cannot be fixed for that.

Yet the exchange still makes sense.

It made me wonder who decides the value of things in this world.”

“So at Saniwa, even if a child has only one hundred yen, I think about what that hundred yen means.

Wanting to serve tea is about the weight of connection, not price.”

Terada-san, now thirty-six, says,

“I want young people to know the value of slowing down.

Just like appreciating art slowly, pause in nature and daily life.

Then you can notice what you could not see before.”

The sound of sipping tea, the breeze on the veranda, the smell of soil.

All of them give the feeling of being alive.

Listening to him, I realize life is a series of detours.

From Osaka to Shiga, to the mountains, to Borneo, and finally to tea and gardens.

None were planned. They formed from gentle pushes of coincidence.

If I had not spoken to him in that Nagano hot spring, this story would not exist.

But coincidences always arrive looking like fate.

Time spent at Saniwa is where such coincidences take shape.

In that space connecting people, past and future,

Terada-san still lives straight, tying his resolve each day.